What is a “Stop data monitoring scheme” and why is it important for public health?

Our understanding of this pandemic has largely been driven by data. Public health data has informed government decision-making and helped the public understand the crisis. Hospitals, public and private agencies and authorities have been regularly and rigorously providing de-identified patient and demographic data to authorities and to media to be analysied and interpreted. “Flatten the Curve” quickly became a unifying concept in how we are to fight the virus. Locally and globally our efforts to prevent the spread of the virus has been determined by how we have been able to access, interpret and make decisions based upon data.

When Victoria’s Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commissioner, Kristen Hilton, called on police in the state to collect demographic data on those being fined and for the information to be released to an independent oversight body she was describing a critical accountability tool slowly being implemented around the world in order to track if and how police are enforcing laws in way that positively impacts upon the public health priorities, or in a way that undermines them.

“There has to be a very rigorous collection of the data,” the Commissioner told The Saturday Paper. “It allows you to interrogate how certain parts of your force are imposing the fines.”

Since early April, there has been widespread community concern regarding the application of new enforcement powers provided to police under emergency COVID-19 public health restrictions.

Policing has its own public health harms. Even if entirely lawful and procedurally correct, policing can result in injuries, anxiety, stress, exacerbation of mental health, fears which restrict people’s lawful use of public space, and, notably during these times, increase the risk of transmission by forcing confinement in cars, interview rooms and cells. If applied in a discriminatory way, such as when policing decisions are informed by bias, stereotypes or prejudices, the severe psycho-social harms upon those experiencing it daily, including upon health, education, employment and housing are well documented and lifelong. Furthermore, if policing, such as patrolling, warnings or the enforcement of fines, is being applied in situations where education, support or other interventions by local youth workers may have been more effective, it can be damaging to our overall efforts to combat the virus. It warrants scrutiny.

The Commissioners’ call is being backed by an increasing number of community, legal and human rights advocacy agencies, including Amnesty International, concerned about the growing evidence that policing of lock-down restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted certain communities more than others.

Over the past five weeks there have been reports of intense police raids of houses in Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, of huge numbers of stops and strip searches of young African background kids in North Melbourne, of a young African-Australian man being fined twice in two consecutive days, of homeless people being arrested and fined for being outside. It is reasonable to ask who is currently more likely to be approached by police, who is more likely to be given a stern warning than polite chat, who is more likely to be fined than warned.

The stories coming through the covidpolicing website only give us snapshots of what is going on, but these sometimes disturbing accounts and the questions they raise have given urgency to the call for a comprehensive police-stop data monitoring scheme. When many thousands of COVID-19 stops are being made by police every day, it is only the police’s own data that can tell us what is really going on.

What a stop-data monitoring scheme would look like

Firstly, police command must take this seriously. What you measure – you care about, and appropriate time and resources need to be provided by police and government to ensure a stop-data monitoring scheme is established with academic level rigor. The responsibly to ensure that these extraordinary COVID19 powers are being used fairly and lawfully rests with police command. This is not a public relations exercise.

Police command must require all police officers collect ‘specific data’ to be entered into police data systems whenever they stop, question or issue a warning to a person in regarding to COVID-19 public health restrictions. Specific data should include; officer perceived race/ethnicity of the stopped person, reason for the stop, location, time, and outcome of the stop.

Secondly, that police make available, or a regular daily or at least weekly basis, de-identified datasets on the locations and circumstances of COVID-19 related stops, fines and enforcement measures taken, in order for the data to be appropriately analyzed and cross-referenced with demographic data by an appropriately qualified independent body.

This independent body could be the state’s human rights commission, Ombudsman, police oversight authority or crime statistics agency. If required, we recommend an appropriate university research team be contracted to assist. To ensure this scheme works, analysis must be independent.

An appropriate memorandum of understanding should govern this data transfer that will permit the public reporting of the analysis of this data. Police will need to provide data with detailed interpretive notes. Professional statisticians within the police should provide every caveat and detail about how the data has been collected so the independent body can correctly interpret their tables.

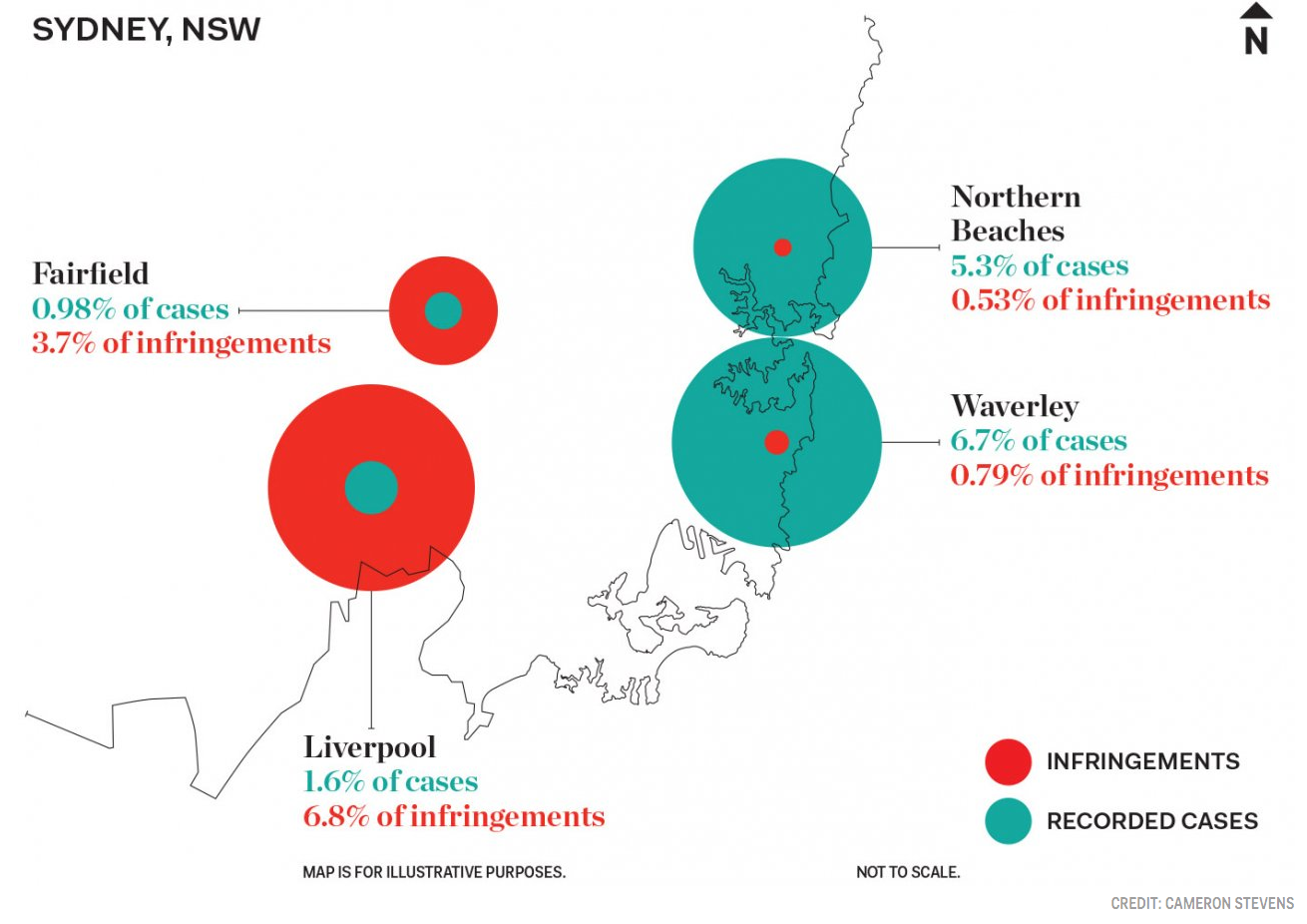

A range of data analysis methods will be needed including comparing stop and enforcement rates against resident populations, analysing the outcomes or ‘hit rate’ of COVID19 related stops in conjunction with an analysis of the presence of ‘reasonable grounds’ before a person is stopped/ warned or fined.[1] It may also be useful to map COVID19 infection hotspots with police stop locations. While this would not create ‘reasonable grounds’ in itself for a stop, it can assist in ensuring that the location of police deployment decision-making is legitimate.

Much of the data required for this scheme would be already being collected by police. The scheme will require this data to be mandatory and monitored to ensure that officers are recording their genuine reasons for stopping / warning or fining people and that these are meeting the relevant initiation standard.

“To tackle this problem, we have to have a mechanism to measure its extent. In order to meaningfully track and tackle the extent of racial profiling, Victoria Police must take the essential step of gathering and reporting on data about the ethnicity of people stopped by police,” said Police Stop Data researcher, Tamar Hopkins.

“Gathering and publicly reporting on data about the race or ethnicity of those targeted for stops by police is already in practice in a number of other jurisdictions, including in the UK and Canada. It is an essential accountability measure, and given the history of racial profiling by police in Victoria and the impact of this on individuals and communities, it is vital that now we implement this here.”

Why police data monitoring is important.

The Australian public has a right to expect that that people will be treated fairly and police discretion will be used appropriately throughout this crisis. The transparent analysis of police data is the only way to ensure this. Ethical and professional standards are critical during this public health crisis. As such, police command must focus on, measure and work to reduce incidents of police-caused harm to the public, human rights breaches, and any unlawful, inappropriate or unnecessary conduct.

It is widely acknowledged internationally that the collection and transparent and independent analysis of police stop and enforcement data is the most reliable way of determining if a particular policing strategy is being applied in a non-discriminatory and therefore lawful way.[2]

The benefits of transparent data monitoring during this period of emergency policing are clear: The public, authorities, media and specific communities are provided with information that can either inform or dispel their concerns. Further, police managers and accountability institutions are provided with the information needed to ensure operational settings, training and instructions are appropriate and are being put into practice.

If policing is to remain aligned with public health priorities over the course of the pandemic we need to make sure we have a detailed understanding of how these important public health measures are being enforced.

The benefits of transparent data monitoring during this period of emergency policing are clear: The public, authorities, media and specific communities are provided with information that can either inform or dispel their concerns.

But this data monitoring must continue beyond the end of the COVID-19 restrictions. Everyone has a right and an expectation to be able to use public space without being treated with suspicion, asked to account for where they are going or told to ‘move-on’ simple because they fit a stereotype. Without addressing this core transparency and accountability issue, discriminatory policing will continue to impact those who get stopped in parks, libraries, train stations and driving on our roads – pandemic or no pandemic.

Police Accountability Project.

Tuesday 12 May, 2020

[1] See for eg Tamar Hopkins, Monitoring Racial Profiling Introducing a Scheme to Prevent Unlawful Stops and Searches by Victoria Police A Report of the Police Stop Data Working Group (Police Stop Data Working Group, 2017).

[2]NAACP National Criminal Justice Program, Born Suspect: Stop-and-Frisk Abuses & the Continued Fight to End Racial Profiling in America (2014); Frank Baumgartner, Derek Epp and Kelsey Shoub, Suspect Citizens, What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us about Policing and Race (Cambridge University Press, 2018); Ontario Human Rights Commission, Policy on Eliminating Racial Profiling In Law Enforcement (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 20 June 2019); Rebekah Delsol, Addressing Ethnic Profiling by Police: A Report on the Strategies for Effective Police Stop and Search Project (Open Society Justice Initiative, 2009); Hopkins (n 1).

Compliance fines under the microscope, Osman Faruqi, The Saturday Paper, 18 April, 2020

“A coalition of legal services, co-ordinated by the Flemington and Kensington Community Legal Centre, has written to police commissioners around the country, calling on a uniform approach to data collection and oversight…

Concerns police using coronavirus powers to target marginalised communities in Australia, Jarni Blakkarly, SBS News, 12 April 2020

“Legal advocates and researchers have urged police to issue more police data and provide clearer guidelines on how fines are being issued for the breach of coronavirus-related public health regulations in each state and territory. The call comes amid concerns that culturally diverse and low socio-economic groups are bearing the brunt of the police actions…

The Monitoring Racial Profiling report released in 2017 by a coalition of academic experts, commissioned by Flemington & Kensington Community Legal Centre, found that introducing a scheme to collect and publicly report on data about police stops is a critical first step in reducing disproportionate stops of people of colour and unlawful stops by police.

Download a copy of the report here (PDF).