How can we make human rights central to IBAC decision-making? Tamar Hopkins discusses the opportunities

When it was enacted ten years ago, section 10 of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) (“Charter”) presented an opportunity to change the way the Office of Police Integrity (“OPI”), and now the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (“IBAC”) investigated complaints against Victoria Police. Recent decisions involving Nassir Bare by the Victorian Supreme Court in 2013 and Court of Appeal in 2015 undermined this opportunity. Fortunately, the Victorian Government’s acceptance of recommendation 26 of the 2015 Charter Review has re-invigorated the opportunity for section 10 to fulfil its potential.

But as a study of IBAC’s Operation Ross reveals, there appears to be a lack of interest in human rights by IBAC’s leadership that goes beyond its interpretation of section 10. This contrasts with the approach taken by the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission to police investigations. A significant cultural shift may be needed in IBAC to make human rights relevant.

Genuine compliance with human rights involves a re-design of IBAC’s approach. Critically this requires IBAC to become “victim-centred”. This in turn will support human rights compliance by Victoria Police.

In early 2017, the Victorian Parliamentary IBAC Committee will be considering IBACs role in the investigation of complaints against police. This, in conjunction with the implementation of the Charter Review, offers the exciting opportunity for Victoria to lead the way in the investigation of complaints against the police: its human rights focus taking it beyond the developments unfolding in NSW.

Section 10 of the Charter

Section 10 of the Charter is derived from Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[2] (the ‘ICCPR’). The relevant provisions of s 10 of the Charter are:

“Protection from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment

A person must not be—(a) subjected to torture; or (b) treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way; or (c) ….”

For convenience, I refer to this as “the right to freedom from ill-treatment”.

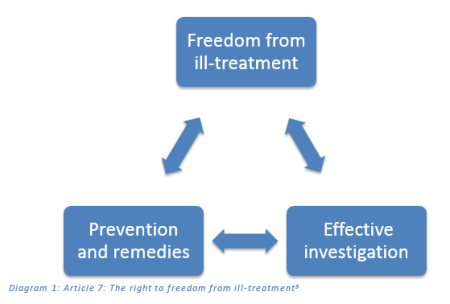

Under the ICCPR, the right to freedom from ill-treatment, when read in the context of the Covenant has a whole, has three components. The first is the substantive protection: that is the prohibition on ill-treatment itself.[3] The second is an implied procedural protection. This is the right to an effective and independent investigation of credible allegations of ill-treatment. [4] The third quality is a preventative obligation on the State. [5] It requires the State to ensure future violations will not occur and that consequences flow to the victim[6] and perpetrator/s. [7] The second and third qualities of the right make it meaningful. These qualities are also found in the interpretation of equivalent provisions in the Human Rights Act 1988 (UK) and the European Convention of Human Rights.[8]

Diagram 1: Article 7: The right to freedom from ill-treatment[9]

Bare v IBAC

Bare v IBAC[10] is the first case[11] to be decided in Victoria (or the ACT which contains an equivalent provision in its Human Rights Act 2004), on whether s 10 of the Charter contains the implied procedural components read into Article 7 of the ICCPR. In 2009, Nassir Bare, a 17 year old Ethiopian Australian alleged that members of Victoria Police stopped the car he was in, pushed him against it, handcuffed him, kicked his legs out from under him causing him to fall to the ground, pushed his head into the ground causing his chin to hit the gutter, grabbed his head pushing his head into the gutter causing his teeth to be chipped, sprayed him in the face with capsicum spray, kicked him in the ribs and said, “you black people think you can come to this country and steal cars. We give you a second chance and you come and steal cars.”[12]

Mr Bare wrote to the OPI requesting that it investigate his allegations as they triggered an obligation on the State to independently and effectively investigate his complaint. The OPI refused to investigate his allegations. Mr Bare appealed this decision to the Supreme Court. VEOHRC joined the case as an independent intervener. The Supreme Court dismissed Mr Bare’s appeal. Mr Bare then appealed to the Victorian Court of Appeal (the “VCA”). By this stage, IBAC became the respondent to the appeal.

The VCA found that there was no implied procedural right to an effective investigation inherent within s 10 of the Charter. It came to this view on the basis that the procedural qualities of the right that exist in equivalent international provisions are supported by enabling provisions that do not appear in the Charter.[13]

In contrast, the European Court of Human Rights states:

“[The right to freedom from ill-treatment] requires by implication that there should be an effective official investigation…Otherwise, the general legal prohibition on torture and inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment would, despite its fundamental importance, be ineffective in practice, and it would be possible … for agents of the State to abuse…rights..with virtual impunity…”[14]

Similarly UK Courts have implied procedural qualities into international equivalents:

“It seems to me that the obligation to have an investigation in circumstances such as these is not so much a secondary procedural obligation but rather part of the positive obligation..”[15]

As Human Rights Committee[16] decisions and European Court of Human Rights decisions[17] commonly (but not always)

Nassir Bare. Photo: Pat Scala

refer to the right to freedom from ill-treatment as being the source of both substantive and procedural rights, it is arguable that the VCA took a narrower approach than was possible. Indeed a broader approach may have been more consistent with an earlier principle adopted by the Court.[18]

While the VCA did not find that there was a procedural right to an effective investigation in s 10 of the Charter, it nevertheless found an obligation on the OPI to consider the human rights outcomes of its decisions.

The VCA found that the OPI had breached its obligation under s 38(1) of the Charter to give “proper consideration” to human rights. The VCA found that the OPI assessing officer did not undertake the required evaluative assessment[19] when he came to his conclusion.

Warren CJ said that the officer failed (amongst other considerations) to:

“Consider how a decision not to investigate would continue to interfere with the appellant’s rights” and “…the potential for a continued threat to the community that could flow from a decision not to investigate”;[20]

Interestingly, at least two of the considerations the OPI officer was held to have failed to take into account, involved Mr Bare’s procedural rights under a broader interpretation of s10. With the VCA reading out the procedural aspects of s10 from the Charter, its continuing requirement that the OPI consider the effectiveness of any investigation and the risks of a failure to investigate, leaves room for debate about IBAC’s continuing obligations under the Charter when it receives complaints raising human rights. Does the proper consideration requirement in s38 of the Charter effectively require IBAC to consider of all three dimensions of the right to freedom from ill-treatment?

Possibly in light of this confusion, in 2015 IBAC decided to investigate Mr Bare’s allegations. With six years between the incident and its investigation, it is not surprising that IBAC found Mr Bare’s allegations unsubstantiated.[21] Delay can cause a range of issues for investigations. For example, any available CCTV evidence would have been gone, injuries may have healed without having been adequately photographed and documented, witness memories can fade, witnesses can go overseas and delays can provide opportunities for collusion among officers.[22]

While the VCA has interpreted s 10 as having no (clear) procedural content, Australia and all its jurisdictions are obliged under the ICCPR, to implement the procedural aspects of the right to freedom from ill-treatment. Under the ICCPR, the state must independently and effectively investigate credible allegations of ill-treatment by police. In a positive step in this direction, and following the recommendations of a Charter review, in 2016, the Victorian Government has agreed to:

“ensure the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission has capacity to investigate allegations of serious human rights abuses by police and protective services officers”[23]

Ensuring capacity in IBAC indicates a commitment to both increased resources and legislative amendment. In 2017, when Victoria’s Parliamentary IBAC Committee further examines the role of IBAC with respect to police complaints, it will have the opportunity to consider not just IBAC’s capacity to investigate allegations of ill-treatment but its capacity to do so effectively. The meaning of effective investigation is the subject matter of the following section.

IBAC’s “Operation Ross”

On 14 and 15 January 2015, a woman (later discovered to be a police officer on sick leave), known as Person A[25], was arrested for drunkenness in Ballarat Victoria and taken to the Ballarat Police Station. It was alleged by counsel assisting the IBAC Commissioner that members of Victoria Police mistreated Person A by unnecessarily stomping on her ankles, kicking her and removing her lower clothing including underpants while she was hand-cuffed, face down and suffering the ill-effects of a large dose of capsicum foam. It was further alleged that police officers failed to check the temperature of the shower she was then placed under for 30 minutes and left her in wet clothing for a lengthy and unnecessary time in very cold conditions. Counsel assisting further alleged that police officers unnecessarily dragged her through a station when it would have been possible to have her walk instead.[26]

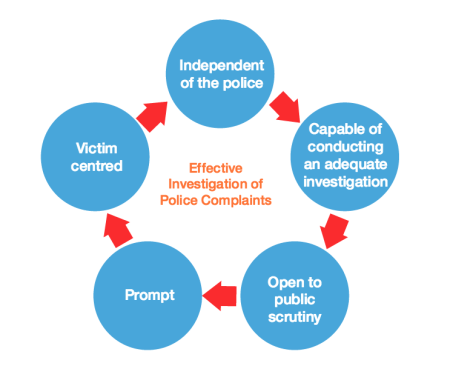

These allegations fit squarely within the definition of s 10 of the Charter, being cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment or punishment.[27] Under the ICCPR such allegations trigger Person A’s right to an independent and effective investigation.[28] Under international law, an independent and effective investigation has five elements.[29] These are identified in the following diagram.

Diagram 2 Effective Investigation of Police Complaints[30]

Was Operation Ross an effective investigation?

Operation Ross was an IBAC investigation into Person A’s allegations that included a four day public hearing at the Ballarat Magistrates Court from 23 to 27 May 2016. The hearing was presided over by the IBAC Commissioner assisted by two senior members of the Victorian Bar acting as counsel assisting. Barristers represented the Chief Commissioner of Police and each police officer being questioned. Person A, the target of the abuse, was not represented. Counsel assisting questioned members involved in the incident as well as members from Professional Standards Command who handle complaints.

Operation Ross was an IBAC investigation into Person A’s allegations that included a four day public hearing at the Ballarat Magistrates Court from 23 to 27 May 2016. The hearing was presided over by the IBAC Commissioner assisted by two senior members of the Victorian Bar acting as counsel assisting. Barristers represented the Chief Commissioner of Police and each police officer being questioned. Person A, the target of the abuse, was not represented. Counsel assisting questioned members involved in the incident as well as members from Professional Standards Command who handle complaints.

The first requirement of an effective investigation is that an investigation be independent of police.[31] While it appears that Operation Ross is an IBAC investigation into Person A’s complaint, the reality is that Victoria Police did the initial investigation. Furthermore IBAC believed it was Victoria Police’s role to consider charging the police alleged to have committed offences with relevant summary offences before the expiration of the 12-month limitation period[32]. Thus while IBAC conducted the public inquiry, Victoria Police played a significant role in the investigation and its outcomes.

The second international requirement is that the investigation be capable of leading to disciplinary or criminal outcomes.[33] IBAC did not take responsibility for ensuring that the police were charged with any relevant summary offence within the 12 month limitation period set out in the Summary Offences Act 1958 (Vic) (“SO Act”). Neither did Victoria Police[34]. While the final outcome of Operation Ross is currently unknown, the failure to charge summary offences within the limitation period is potentially a serious defect in the adequacy of the investigation.

While there are still opportunities for disciplinary or Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) offences to be charged, Operation Ross missed some critical opportunities to explore failures with respect to human rights abuses. Indeed, despite the function of IBAC in s15(3)(b)(iii) of the IBAC Act to ensure that Victoria Police have regard for human rights under the Charter, other than cursory questions about privacy, not one question, directly relevant to human rights as set out in the Charter was put to any of the officers giving evidence for Operation Ross.

Relevant questions include for example, “What consideration did you give to Person A’s right to freedom from inhuman treatment when you kicked her?” or “What consideration did you give to Person A’s right to dignity when you removed her underpants?”

Section 38 of the Charter requires public authorities including Victoria Police and IBAC to give proper consideration to human rights in their decision-making. Her Honour Tate J states:

“for a decision-maker to give ‘proper’ consideration to a relevant human right, he or she must: (1) understand in general terms which of the rights of the person affected by the decision may be relevant and whether, and if so how, those rights will be interfered with by the decision; (2) seriously turn his or her mind to the possible impact of the decision on a person’s human rights and the implications thereof for the affected person; (3) identify the countervailing interests or obligations; and (4) balance competing private and public interests as part of the exercise of justification.”[35]

IBAC is not only obliged to consider Person A’s human rights in its decision making (indeed it is unlawful[36] for it to fail to), but through section 15 of its own Act, it is required to ensure Victoria Police properly have regard to human rights. In my opinion, the questioning of officers during Operation Ross missed important opportunities for IBAC to properly consider human rights and to ensure Victoria Police have proper regard for human rights.

While IBAC’s report into Operation Ross released 9 November 2016, did identify human rights breaches and made non-specific recommendations to Victoria Police in relation to human rights, it is curious that none of the officers were probed about their knowledge of human rights at the hearing. The failure to probe these issues at trial suggests a lack of relevance to IBAC.

Operation Ross’s capacity to meet the third and fourth standards required in an effective investigation set out in Diagram Two above –that is public scrutiny and promptness – were partially impacted by Victoria Police members’ decision to challenge IBAC’s decision to hold a public hearing in the High Court of Australia[37]. While the High Court decision ultimately paved the way for a public hearing, the delay did have consequences. Had IBAC or Victoria Police taken responsibility for charging the officers within the Summary Offences Act limitation period some of the issues around delay could have been mitigated.[38]

The final requirement of an effective investigation relates to the involvement of the victim. The Operation Ross transcript reveals that IBAC took minimal steps to protect the interests of Person A or to involve her in the investigation. Person A did not have access to the footage of her mistreatment until IBAC released it to the public on 25 May 2016 during the course of the public hearings. Council assisting the IBAC Commissioner did not put Person A’s version of events to the officers being questioned in the public hearings. Person A was not represented at the hearing, nor entitled to ask questions of the witnesses. She was not provided with critical information. In fact Person A’s experience, other than as a hapless body appearing on CCTV footage, was not present at all. The fact that she is a living, rights-bearing person appeared irrelevant.

Indeed it became apparent during the hearing that despite all the issues of delay effecting their capacity to charge the police involved, Victoria Police had taken steps to ensure that Person A was charged within the 12 month limitation period under the Summary Offences Act.[39] The differences in the way the rights of the officers and target were treated could not be more apparent.

Through an examination of what is currently known about IBAC’s Operation Ross, it appears that IBAC is not concerned with the five elements of an effective investigation set out in Diagram Two. Nor however does it appear that IBAC is concerned with the proper consideration of rights required in Bare. For some reason, it appears that IBAC has missed the cultural changes the Charter is intended to bring.[40]

How does the VEOHRC conduct inquiries into police conduct?

In 2015, the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission issued the first report into its “Independent Review into Sex Discrimination and Sexual Harassment including predatory behaviour into Victoria Police”. The Commission’s investigation, conducted at the invitation of Victoria Police, concerned allegations by Victoria Police members about police conduct many of which were s10 Charter ill-treatment allegations: the most serious being the alleged rape of a female police officer by a male police officer. While the Commission is not empowered to take disciplinary or criminal action against alleged offenders, it was able to investigate in a way that led to a record number of Victoria Police members coming forward to give evidence. Indeed the Commission reports that it is the largest inquiry into sexual harassment and discrimination of an organisation outside the US Army in any part of the world.[41]

The inquiry made numerous recommendations to Victoria Police. In particular, it recommended that Victoria Police “implement…a response to harm that puts the victim at the centre of the process, rather than the investigation.”[42]

Another recommendation called for: “Improving actions and outcomes of formal processes, so that the victim is supported throughout the process, complaints are resolved in a consistent and professional manner and steps are taken to stop similar inappropriate behaviour occurring in the organisation.”[43]

The recommendations “include…strategies to diversify and professionalise the workforce and the new victim-centric service delivery model plan, Future directions for victim-centric policing.”[44]

The Victoria Police’s Chief Commissioner openly acknowledged, “We could have undertaken an internal review but that wouldn’t have led to systemic change. We need change more quickly. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.”[45]

The comment from the Chief Commissioner is illuminating. And his views are not alone within Victoria Police:

“It is not just about sexual or predatory behaviour. Police should NOT investigate police (male survey respondent).”

“Stop internal investigations against those with a badge looking like a cover up (ie: nothing is ever thoroughly investigated against a sworn member when it is conducted by another sworn member) (male survey respondent).”[46]

Concerns about the lack of independence of police decision makers in relation to complaints against police raised by respondents to the Commission’s inquiry reflect similar concerns consistently raised elsewhere.[47]

The Commission inquiry is revealing for a number of reasons. Unlike the Victoria Ombudsman when investigating sexual assault allegations against police officers by members of the public in 1997[48], the Commission’s inquiry was able to maintain the trust and confidence of large numbers of the targets of ill-treatment and police members who had witnessed this ill-treatment. This has much to do with its independence from Victoria Police. But it is equally due its victim-centred approach to investigation. Its example is highly relevant to IBAC investigations: victims need to be supported and made the centre of the investigation process. Indeed, it would be sensible for IBAC to develop its own victim-centred service delivery model plan to overcome one of its failings in Operation Ross.

Police Complaints Clinic 2015 report

The Flemington & Kensington Community Legal Centre recently released a report on its 2015 Police Complaints Clinic.[49]

The Flemington & Kensington Community Legal Centre recently released a report on its 2015 Police Complaints Clinic.[49]

The report’s concerns with IBAC include a lack of transparency about the allegations IBAC investigates, its failure to provide reasons to complainants about decisions, its secrecy about investigative information and its almost universal failure to investigate allegations made to it. IBAC’s failure to provide natural justice to complainants is contrary to law. The decision in Bare v IBAC confirms IBAC’s obligation to provide natural justice to complainants.[50]

Each of the concerns raised by FKCLC points to the lack of concern IBAC has with international human rights obligations. But they also indicate its failure to grapple with its obligations under ss10 and 38 of the Charter.

Conclusion

All is not lost. The Victorian Government’s commitment to implementing recommendation 26 of the Charter Review and the forthcoming Victorian Parliamentary IBAC Committee’s focus on the investigation of police complaints in 2017 offers the opportunity to make human rights central to IBAC decision-making. Importantly, the IBAC Committee has indicated its interest in hearing from the wider community.

The Committee must consider two critical questions. Which rights infringing allegations should be investigated by IBAC?[51] Just as importantly, how should IBAC investigations be conducted?

This is a critical opportunity for the Committee to recommend that Parliament implement its obligations under the ICCPR to effectively, transparently, promptly and independently investigate complaints in a way that involves the targets of human rights abuses.

The simple act of dignifying the targets of human rights abuses in the investigation offers an important counter-balance to the powerful criminalising and dismissing narratives offered by perpetrators and their supporters about those who complain. Providing this counterbalance requires a new institutional approach: placing the targets of human rights abuses at the centre of the investigation process.

As suggested above, IBAC could develop a victim-centred service delivery plan that will enable it to support targets through the process, ensure their confidentiality (where requested), allow their participation, and provide them with information and the right to ask questions through counsel at hearings.[52] This plan could also ensure that IBAC provides complainants with natural justice and reasons for its decisions. These reasons should reflect a proper consideration of human rights as set out by the Court of Appeal in Bare.

Given the Bare ruling, and in keeping with Charter Review, legislation is needed to ensure IBAC meets each of the five standards set out in Diagram Two. [53] One way to do this is to amend s10 to refer expressly to a person’s right to an independent and effective investigation in response to a credible allegation of ill-treatment. Alternatively, Parliament could insert an enabling provision such as Article 2 of ICCPR into the Charter. Additionally the five investigation standards can be legislated directly into the IBAC Act.

Tamar Hopkins

Tamar Hopkins

Tamar is the former Principal Solicitor at the Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre and founder of the Police Accountability Project.

November 2016

[1] Unpublished article

[2] Opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976)

[3] United Nations Human Rights Committee, General Comment 20: Article 7 (Prohibition of Torture, Or Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment) 44th sess. UN Doc A/44/40 (10 March 1992).

[4]See for example, Ibid [14] and United Nations Human Rights Committee, UN Doc. Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 40 of the Covenant : International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights : concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee : Australia, UN Doc CCPR/C/AUS/CO/5 (7 May 2009) [21] and Tamar Hopkins “Effective investigation of complaints against police” (2009) < https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/VLF-REPORT-Effective-Investigation.pdf>

[5] Above n 5 [11][14].

[6] Human Rights Committee, Views: Communication No. 1885/2009, 101th Sess. U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/110/D/1885/2009, (5 June 2014) [10] ‘Horvath v. Australia’.

[7] Human Rights Committee, General Comment 31 [80], The nature of the general legal obligation imposed on States Parties to the Covenant, UN Doc CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13 (26 May 2004) [18].

[8] Council of Europe, European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as amended by Protocols Nos. 11 and 14, 4 November 1950, ETS 5, Article 3.

[9] Author’s diagram.

[10] [2015] VSCA 197 (29 July 2015).

[11] On appeal from Bare v Small [2013] VSC 129 (25 March 2013).

[12] Ibid [5][6].

[13] It concluded that Article 7 of the ICCPR relies on Article 2 and Article 3 of the ECHR relies on Article 13 to incorporate procedural requirements.

[14] Hajrulahu v The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia [2015] ECHR 960 (29 October 2015) [68].

[15] JL, R (On the Application of) v Secretary of State For Justice [2008] UKHL 68 (26 November 2008) [26].

[16] Human Rights Committee, Communication No 1945/2010, 107th sess, UN Doc CCPR/C/107/D/1945/2010 (27 March 2013) (‘Maria Cruz’).

[17] Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs, Council of Europe, Effective Investigation of Ill-Treatment: Guidelines on European Standards (2009), 27.

[18] This was argued in submissions by VEOHRC. Re Application under the Major Crimes (Investigative Powers) Act 2004 (2009) 24 VR 415 [80] (7 Sepetember 2009) Warren CJ.

[19] Castles v Secretary to the Department of Justice & Anor (2010) 28 VR 141 [185], see the argument of the VEOHRC available at <

[20] Bare v IBAC [2015] VSCA 197 (29 July 2015) [221], see also [541] Santamaria J.

[21] IBAC, ‘Independent investigation finalises 2009 police assault allegations’, (2016) < http://www.ibac.vic.gov.au/news-and-features/article/independent-investigation-finalises-2009-police-assault-allegations>

[22] See for example Tamar Hopkins ‘Effective investigation of complaints against police’ (2009), 49 < https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/VLF-REPORT-Effective-Investigation.pdf>

[23]Victorian Government, ‘The Government Response to the 2015 review of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act’ 2016, Recommendation 26 <http://www.justice.vic.gov.au/home/justice+system/laws+and+regulation/human+rights+legislation/government+response+to+the+2015+review+of+the+charter+of+human+rights+and+responsibilities+act>

[24] The name “Ross” is not meaningful. It is the randomly assigned name of an investigative operation conducted by IBAC.

[25] Person A has subsequently revealed her identity as Yvonne Berry, ABC 7:30 18/10/2016, <http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2016/s4558932.htm>

[26] Transcript of Proceeding, IBAC Operation Ross, Jack Rush, (23- 24 May 2015) <http://www.ibac.vic.gov.au/investigating-corruption/our-investigations/operation-ross>

[27] They also trigger issues under Charter ss 8 (equal treatment by the law), 22 (1) (the right to humane and dignified treatment when deprived of liberty) and 17 (the right to privacy).

[28] Corinna Horvath v Australia, Communication No. 1885/2009, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/110/D/1885/2009 (2014), [8.2].

[29] AM & Ors, R (on the application of) v Secretary of State for the Home Department & Ors [2009] EWCA Civ 219, 9. See also Graham Smith, (2008) “European Commissioner for Human Rights Police Complaints Initiative” – 172 JPN 399, 1,2.

[30] Amended diagram from Police Accountability Project “Independent Investigations of Complaints Against Police, Policy Briefing Paper” (2015) < https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CLCpaper_final.pdf>

[31] Ramsahai v The Netherlands [2007] ECHR 393 (15 May 2007) [325], [337]. Nachova and Others v Bulgaria [2005] [GC] ECHR (6 July 2005) [112], Bati v Turkey [2004] ECHR (3 June 2004) [135].

[32] Transcript of Proceeding, IBAC Operation Ross, Tony De Ridder, 27 May 2016, 6,7.

[33] Jordan v The United Kingdom [2001] ECHR 327 (4 May 2001) [107].

AM (on the application of) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2009] EWCA Civ 219 (17 March 2009) p 9.

[34] Above n 28.

[35] Bare v IBAC [2015] VSCA 197 (29 July 2015) [288].

[36] Charter s 38.

[37] R v IBAC 2016 HCA 8 (10 March 2016).

[38] Above n 28.

[39] It has subsequently been revealed that charges against Person A were dropped: ABC, 7:30 October 2016 <http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2016/s4558932.htm>

[40] George Williams, ‘A Human Rights Act for Queensland?’ (2016) 41 Alternative Law Journal 81, 81 [7].

[41] VEOHRC, ‘Independent Review into sex discrimination and sexual harassment, including predatory behaviour in Victoria Police: Phase One Report – Dec 2015’, (2015), 2.

[42] Ibid, also see Ibid 15.

[43] Ibid 19.

[44] Ibid 43.

[45] Ibid 41.

[46] Ibid 379.

[47] See for example Houston Vedelago, “Prosecutions office overrules assistant commissioner on police assault case” The Age (online) 23 June 2016 <http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/prosecutions-office-overrules-assistant-commissioner-on-police-assault-case-20160622-gppgt1.html> and Police Accountability Project “Independent Investigations of Complaints Against Police, Policy Briefing Paper” 2015 < https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CLCpaper_final.pdf>

[48] Victorian Ombudsman, “The Maryborough Police Inquiry” 1997, <https://www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/getattachment/3135bcad-1e66-4abd-b5d1-4913528ba58c>

[49] Julian McDonald, Tamar Hopkins, Police Accountability and Human Rights Clinic, Report on the First Year of Operation, 2016, Police Accountability Project, FKCLC, <https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/racial-profiling/launch-of-police-complaints-clinic-report/>

[50] Bare v IBAC,[2015] VCA 197 29 (July 2015) [556, 566] Santamaria J.

[51] See Stoica v Romania [2008] ECHR 191, (4 March 2008) [60], [61] and see n 21, 25-28.

[52] See n 21, 81-100.

[53] A full set of recommendations can be found can be found at n 21.

Tamar Hopkins is the former Principal Solicitor at the Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre. She has focused on police complaints and racial profiling for over 10 years and has published numerous articles and reports on policing and human rights.

“Genuine compliance with human rights involves a re-design of IBAC’s approach. Critically this requires IBAC to become “victim-centred”

“The first requirement of an effective investigation is that an investigation be independent of police.”