10 things you need to understand about the media and crime reporting in Victoria right now

30 December 2017 (updated 8th February 2018)

Media coverage of crime involving African young people is in hyper-drive in Victoria at the moment. Why do some crime incidents, which have very different dynamics and causal factors, receive national media attention and breathless, repetitive commentary when similar incidents involving Caucasian young people didn’t?

Why do politicians and commentators speak about “out of control” crime when the latest crime data shows we are safer than we have been in a decade?

If you are wondering whether we really are in the grip of an ‘African Youth crime wave’ then here are ten handy and important points to consider.

1) These incidents fit into a bigger story

These were not the only crimes occurring over December in Melbourne. Nor were they the worst. But the attention they are receiving is extraordinary. Full-spectrum coverage, multiple stories and follow-up articles. What is happening here? The idea that ‘African/ethnic youth’ are driving a massive crime wave has grown inexorably since March 2016 when the tabloid media, the state opposition, far-right and anti-immigration groups finally had a short-hand way of describing it.

When groups of teenagers rampaged through the late-night Moomba event the story of a youth gang called ‘Apex’ fitted perfectly with long held fears of ethnic gangs bringing ‘mayhem and fear’ to our city. Even when post-incident police reports contradicted the ‘gang’ narrative it did not matter.

An existential threat had arisen and it was the African youth gang. Apex became a code word that an ever-increasing number of people, including mainstream politicians, could use without saying ‘African crime gang’. Media coverage since then has largely fitted any story involving people of African appearance’ into this particular frame. It’s been relentless. Some journos have debated its veracity but the association between crime and young people of African, particularly Sudanese, background, has been firmly established. The latest set of incidents are connected by this larger ‘frame’ and have provided sections of our media, during a slow summer news period, with a far bigger story than another out-of-control party or an another assault of a police officer. The story becomes about African youth as whole, about how the police are responding, what the Police Minister is saying, and whose fault it is. It is no longer a crime story but a political story.

The pressure from pundits, community law and order activists, anti-immigration groups and journalists on the police and state government to ‘admit that there is problem with African youth’, is immense. Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, MP Greg Hunt, Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton and other Victorian federal MPs have waded in with comments to blame the Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews amid calls by MP Jason Wood for a Australian Federal Police ‘gang-busting squad’ and his long running calls to deport children. If ever you need an example of how fear of crime is used for political purposes you can come back to this.

2) Journalists tend to follow a script.

Despite its best intentions the media is not neutral. It has biases and is shaped by and shapes public opinion. When choosing which story to cover, journalists, editors and sub-editors tend to follow a particular script. Studies here and in the United States demonstrate how journos have a tendency to cover crimes where a suspect is Black and a victim White. These stories get more prominence, larger headlines and use more exasperated and racialised language (thugs, predators, etc) than typical crime reporting. Black youth are more likely to be described as a ‘gang’ than a group of white youth. Tags like ‘Apex’ and MTS or ‘Menace to Society’ are used both by young males to big-note themselves and by journalists because they fit so well into the script.

Part of this tendency is unconscious bias on the part of journalists but there’s also clear pressure to seek out stories that conform to widely held stereotypes within the media outlet and amoungst its readership.

The journalist Walter Lippmann wrote that societal feelings, beliefs, opinions and actions are responses to “pictures in our heads,” not to the world itself. What we see in the media provides most of these pictures, which, as the majority of crimes being reported on are those involving young people ‘of African appearance’, has created a distortion in the public’s perception of crime.

3) The coverage of ethnicity is selective

Race is not discussed in the media coverage of New Year’s brawls on Phillip Island or schoolies week on the Gold Coast. Knowing that these young people are predominately fair-skinned or Caucasian does not help the police or the community understand or respond to these incidents.

A Bob Jane T-Marts vehicle was rolled over during the riot protesting the cancellation of the EasterNats race meet at Melbourne’s Calder Park Raceway. Photo: Wayne Hawkins

The worst riot in Victoria’s recent history occurred in March 2010 when about 5,000 young people smashed windows, threw flares at police, and overturned cars whilst protesting the cancellation of the EasterNats race meet, causing over $40,000 in damage to Bob Janes T-Mart and nearby businesses. The ethnicity of the rioters in this case was not mentioned in any article, nor were any ‘community leaders’ called up to comment or asked to explain why the overwhelmingly Caucasian youth were so violent. Ethnicity was deemed to be irrelevant to media coverage of that event.

In November 2017 a ‘wild brawl’ broke out at a Gippsland Bachelor and Spinsters Ball in Tooradin. A woman was king hit and ‘stomped on’ as she tried to resuscitate a man who’d been “almost killed”. Four people were hospitalized and police back-up had to be called in from 100km away.

The incident got a story in each of the major papers and it was mentioned on 3AW. The ethnicity of the brawlers, who were entirely Caucasian in this case, was not mentioned. Despite resulting in far more injuries than the brawling at Moomba in 2016 the story was deemed not worth following up by any major media outlet.

There was an unusually rare armed bank holdup in Melbourne Western suburbs in recently, The suspects are decribed as Caucasion. It has recieved no mention in relation to this story.

So, for crimes involving caucasian people, the suspect’s ethnic background is not relevant to mention, but for the same crimes involving people of African background, we hear conjecture and discussion about the backgrounds, culture, community, and the ethnicity of those involved.

A massive brawl at this BNS Ball in Tooradin which hospitalised four people did not lead to an existential crisis for Victoria.

4) We are in the midst of a moral panic

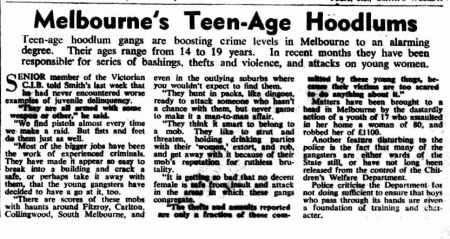

There’s enough research on ‘Gangs, media representation and Moral Panics’ to fill a library or two. In Australia we’ve been here multiple times. In fact the moral panics over the knife wielding Bogies and Widgies youth gangs in the 1950’s and then the Sharpies in the ‘60’s and 70’s led front pages stories and featured iron bars, home made guns and bloody knife fights that make the Moomba brawl of 2016 seem very tame.

The Argus ,13 August 1949

A moral panics are a feature of modern society. They occur when something, usually a negative stereotype or ‘folk devil’, is suddenly perceived as a threat to society’s values and interests and when moral crusaders, experts and politicians wade in with various diagnoses and solutions to the crisis. Ethnic minorities are common targets. The current intense media portrayal of African youth is an adaption of similar racialised scares that focused upon Indigenous Australians, asylum seekers Muslims, and Arabic and Lebanese people.

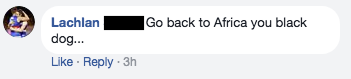

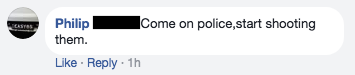

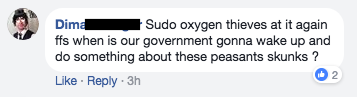

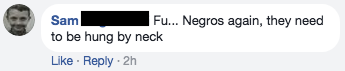

Moral panics tend to be generated by tabloid media and the entry of the online Daily Mail UK into the Australian media space in 2014 brought this sort of specialist expertise. Moral panics gain eyeballs and clicks. Social media and Facebook are now part of the moral panic chain. Everyone is an expert of crime, policing and sentencing practices. Now, we no longer see a crime story on the evening news or in the morning paper. It’s posted multiple times in our news feeds. It’s on our phone at home and on our tablets at work and we may see the same crime story six or more times. It’s enough to make anyone fearful and despairing of the world. It doesn’t matter that different crime types have vastly different causal factors, triggers and dynamics. Collectively they serve to maintain the impression that crime is everywhere, it is out of control and its mainly African youth.

Hey Daily Mail – your Apex Gang pic is actually a UK rap band – image courtesy of ABC Media Watch

5) This sort of media coverage is harmful

Misguided and inaccurate public associations between ethnicity and crime is leading directly to increasing forms of discrimination, including employment discrimination and has well-established psychological harms and social exclusion impacts upon the community itself.

The Refugee Council of Australia recently reported an increase ‘in discrimination, racism and serious assaults against refugees and people seeking asylum’. “Some former refugees have told us that media stereotypes make it difficult for them to engage with the wider community, especially when looking for jobs, and that Australians miss the chance to see what they can do and how they can contribute”.

According to the 2016 annual ‘Mapping Social Cohesion’ survey by the Scanlon Foundation ‘27% of people from non-English speaking backgrounds reporting an experience of discrimination in the past year’ and that out of that cohort ‘31% of those experiencing discrimination report experiencing it about once a month or most weeks in the year’.

The persistent ‘black crime association’ in mainstream Australian society is a key factor in the practice of racial profiling by police, and is born out in well-documented discriminatory policing practices. It leads to the targeting, abusing, terrorizing, harassing and over-policing of African young people. Alongside hate crimes and discrimination racial profiling by police redoubles the sense of vulnerability and acts as a clear form of social exclusion

Critical initiatives to reduce police discrimination such as stop and search data monitoring and receipting are being delayed because of this intense racialised media focus.

It also results in criminalisation (the process in which young people of colour are perceived to be and treated as if they were criminals or likely to become one by police, teachers, social workers and communities.)

Maribyrnong College principal Nick Scott, described this process recently. “Disconnection, feeling like no-one’s in your corner, that you are just being typecast and that there’s no way for you to have any kind of equal footing,” he said. “Generally you don’t have too much trouble as an African boy when you’re nine in terms of society judging you when you walk down the street, but as a 15-year-old young man all of a sudden people tend to get suspicious, every retail experience becomes problematic. Then that treatment, it just brings an attitude of no-one trusts us….I think in part they give up.”

6) Racialised perception of crime serves a purpose.

Racism is always functional. The reporting, commentary, and amplifying on social media of ‘African crime’ serves a set of very specific purposes for a range of groups and political positions in Victoria right now.

Ratcheting up fear of crime drives support for more punitive criminal justice policies, which allows more conservative parties to paint more progressive policies as ‘soft’. The Victorian opposition will be building its law and order agenda as we head to the Victorian State Elections in November. It’s an emotive, destructive and self-defeating form of politics that undermines sound criminal justice policy but they will use it for all its worth nonetheless.

It is also very much in the interests of the far-right, neo-nazi and white-nationalist groups in Victoria who gleefully share and magnify each and every crime report. It feeds their anti-immigration rhetoric and they ensure blame is firmly placed at the feet of ‘the left’, ‘political correctness’ and multiculturalism. The plethora of suburban neighborhood crime groups are a primary platform for recruitment and radicalisation. The racialised framing of crime is the seedbed for their growth and it is how they are building political power right now.

The link between fear of crime and authoritarian politics is an old one. Fear makes people cling to the familiar and regard the unfamiliar more warily. It makes those who promise to ‘protect’ or ‘defend against threats’ look more inviting. It’s why US President Donald Trump consistently depicted outsiders as a frightening threat throughout his election campaign and continues to do so.

Misguided attacks on migration, sentencing practices, bail or parole are common but deeply flawed positions. They demonstrate both ignorance of how the criminal justice system works and the complex factors that generate or reduce crime in society. All they offer a scared population is a false hope in return for votes.

Law and order panics allocate blame, call for vengeful punishment and shift our criminal justice systems away from prevention and rehabilitation into ever increasing and self-defeating cycles of imprisonment and criminiogenic practices. It’s a psychological, cultural and political dynamic that helps generate more crime, reinforce state power and ultimately reduce hard won freedoms.

In the lead-up to Victorian elections, Sudanese young people will be labeled, discussed, generalised and vilified. People will lean into fear based responses until leaders show that crime says more about all of us as a society than it does about any one particular group.

7) There is no ‘African youth’ crime wave

Victoria does not have a youth crime wave – ethnic or not

However, facts and statistics are of little interest to a person already convinced that their intuitive, deeply felt, folk wisdom is enough. Arguing with a ‘tough on crime’ proponent is like arguing with an anti-vaxxer. When the independent Victorian Crimes Statistics Agency released its latest data report in December and stated that overall criminal incidents recorded in Victoria was down 4.8% and significant downward trends in many crime types, much of the online law and order world did not believe it. “Look at the papers” they cried. “We read about crime every day!”

But for everyone else here are some basic stats.

The Bureau of Statistics count of recorded crime across all states shows just 75,860 offenders in 2016-17, down from a high of 87,695 under the Baillieu government in 2012-13 and the fourth successive annual fall.

There were fewer youth offenders than at any time since the turn of the century: 8280, down from 14,757 in 2008-09. (Peter Martin, The Age)

Youth crime rates in Victoria have been slowly declining for more than a decade. Crime Statistics Agency research has shown that most youth crimes are by a small proportion of repeat offenders. Despite this, there’s been a jump in aggravated burglaries and some violent crime types that has got everyone’s attention.

Victorian crimes statistics show a decrease in youth offending rates:

The proportion of incidents committed by alleged offenders under the age of 25 has fallen from half of all incidents recorded in 2007-2008 to 40% of all incidents in 2015-2016.

The number of young people in detention on sentence is also down: sentenced in Children’s Court halved since 2008–09 with only very small number receiving sentence of detention.

Victoria has the lowest rate of children (10-17) under justice supervision on an average day in Australia.

Evidence showed that migrant youth and newly arrived migrants are not involved in criminal activity with less than 10 per cent being overseas born offenders. The second-highest country, after Australia, of alleged offenders in Victoria is New Zealand (2.8 per cent of the total offenders), followed by Indian (1.5 per cent), Vietnamese and Sudanese (both 1.4 per cent).

Victorian Crime Statistics Agency clearly show that the vast majority of offenders in Victoria are Australian born and older than 25. Adults were predominantly the largest proportion of offenders, with 67 per cent over the age of 25. Of those Australian born offenders, a relatively small percentage was comprised of youth offenders: 10 per cent were aged 10 to 17 and 22 per cent were aged 18 to 24 years.

Schoolies week 2016 – there’s no need to mention to ethnicity here.

8) ‘Over-representation’ is a data trick

To claim that current crime rates are being “driven by” any one group is utterly false. What many are confusing us with is an old data trick. An ‘over-representation’ within a small sub-set of figures. Because it’s a newly arrived community, Sudanese young people are ‘over-represented’ within their own tiny demographic, and they are therefore over-represented in some crime types. But their proportion of overall offending remains very small; less than 2% of overall youth crime figures. Sudanese young people not born in Australia make up an even smaller proportion. Aggravated burglaries are not ‘driven’ by the 4.8 percent who happen to be Sudanese.

The statistics show that young people born outside Australia commit a disproportionately low number of crimes. Data obtained from Victoria Police, for example, shows that from 2012–2016, the vast majority of young people aged 10-18 involved in crime were Australian-born. Likewise, a report by the Centre for Multicultural Youth used current police data to show that young people born overseas are less than half as likely to be alleged offenders compared with other young people. [ii]

9) There is no association between race and criminal behaviour

We shouldn’t have to say this in 2018 but we do. There is absolutely no causal link between ethnicity and criminal behavior. This question has been studied by the Australian Institute of Criminology and similar institutes around the world. Consistently researchers find that a person’s ethnicity or race has no determination on their likelihood of being involved in crime. Journalists in particular should be aware of this.

When seeking prevent or reduce criminal behaviour most police and justice agencies recognise that socio-economic factors, gender, age or situational related factors are what needs to be focused upon.

Police, who deal with all crimes in their area, not just the ones that get reported on, have been clear that there is no single ethnicity represented. Victoria Police’s Superintendent Therese Fitzgerald said “youth crime in general”, rather than gangs associated with an ethnic group, was the problem. “We have problems with youth crime across the state and it’s not a particular group of youths we are looking into. It’s all youths. It’s youth crime,” she said when doggedly questioned by reporters seeking to widen the African crime angle.

Wyndham’s chief of police Inspector Marty Allison stated that the cultural backgrounds of those involved was irrelevant. “This is not about ethnicity, it’s not about people’s background, it’s not about religion, it’s about their behaviour, so any conversation that goes on around ethnicity needs to be squashed” he told Fairfax news.

10) We are distracted from real solutions

Everyone in Victoria has a right to feel safe. We also need to do a lot more to reduce violence and crime in our society. But responses to young people engaged in criminal behavior should focus on their youth, and risk factors such as disengagement, family problems, and unemployment rather than their ethnicity or the colour of their skin.

To create safety we need to invest in communities. This means resourcing programs that tackle disadvantage and the causes of crime. We need more drug and alcohol support or mental health services, youth workers and needs-based funding for early childhood services, family support and schools. And we desperately need to challenge societal wide constructions of aggressive masculinity that so many young men are englamoured by.

But we remain distracted from all of this whilst so many are seeking to capitalise on fear and prejudice.

Anthony Kelly is the Executive Officer of the Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre and a co-founder of Smart Justice, a campaign that counters law and order populism.

[i] Windle, J. A. (2008). Mediatised public crisis and the racialisation of African youth in Australia. In T. Lyons (Ed.), 31st AFSAAP Conference (pp. 1 – 21). Melbourne Vic Australia: The African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific.

[ii] Statistics provided as submissions to the Inquiry into Migrant Settlement Outcomes which presented its report on 8 December 2017. No one teaches you to become an Australian December 2017 Commonwealth of Australia 2017

See also:

Reporting Race and Crime: A short Guide for journalists

Smart justice for young people: Investing in communities, not prisons (2017)

This new report, Investing in communities not prisons, explores justice reinvestment and its experience in Australia and internationally. The report includes experiences from many jurisdictions which have faced similar youth justice issues and challenges as Victoria, but looks to different responses involving spending less on prisons and investing more in communities. A great resource for journalists seeking an alternative framing of solutions and approaches to creating safety and reducing crime.

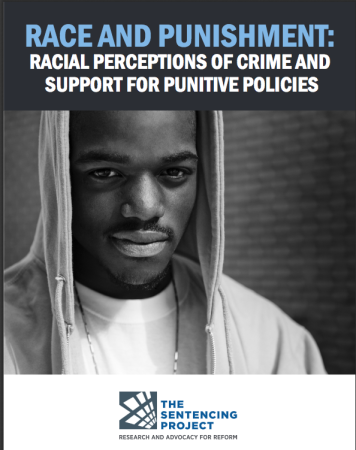

Race and Punishment: Racial Perceptions of Crime and Support for Punitive Policies (2015)

The Sentencing Project report, “Race and Punishment: Racial Perceptions of Crime and Support for Punitive Policies,” by Nazgol Ghandnoosh, PhD, a research analyst at The Sentencing Project, a national non-profit organization engaged in research and advocacy on criminal justice issues. A highly recomended read for all media professionals.

Crime Statistics Agency

The Crime Statistics Agency (CSA) is responsible for processing, analysing and publishing Victorian crime statistics, independent of Victoria Police. The CSA aims to provide an information service to assist and inform policy makers, researchers and the Victorian public. The CSA reports and publications provide longer term analysis and commentary of crime trends.

If you wish to obtain a quote or comment in relation to crime statistics from the CSA or Chief Statistician, contact 03 8684 1808 or send an email to info@crimestatistics.vic.gov.au

For detailed factsheets on effective, evidence-based responses to crime, journalists are encouraged to bookmark : http://www.smartjustice.org.au/cb_pages/factsheets.php

6 Comments

-

Nearly 300 men born in Sudan or South Sudan were arrested in the last financial year, according to Victoria’s Crime Statistics Agency. In raw numbers, it is a small cohort when compared with the 18,770 Australian-born and 658 New Zealanders arrested by police. But compared with 2016 population data, Sudanese or South Sudanese-born people are 6.135 times more likely to be arrested than anyone born here.

-

Author

Hi Mark, yes that is the exact point we made in this article. The Sudanese population in Melbourne, just like the New Zealand population, is incredibly young. Mainstream society has an aging population and is weighted toward the elderly. Within communities so over represented by young people, some proportional over-repesentation in crime is to be expected. It makes total sense that there is this ‘6.135 times more likely’ figure within their small populations (all other significant socio-economic risk factors aside). But as you pointed out their actual numbers are comparatively small. Intense media focus on every crime involing an African person plus some MPs and commentators and media outlets misusing these stats has generated an incredible distortion. These stories get far more coverage, prominence and are more likely to receive the full dramatic treatment by outlets such as A Current Affair. This biased and selective reporting, hyperbolic commentary, and the stereotyping of an entire community of Australians reflects a racial bias pure and simple.

-

-

wow